Expanding a bit from my previous post about growing ginseng, I’ll talk a bit about building an underground house. The correct term is actually an “earth sheltered home” but most folks would call it an underground house. Underground homes can be extremely expensive to build and all you have to do is hire an architect who doesn’t know anything about it. He’ll consult with a civil engineer and you’ll wind up with something that looks like it was designed by the department of defense with a comparable price tag. Fortunately, there’s an easier and much less costly way to do it, using what’s known as “off the shelf” technology.

The basic building block is the ubiquitous shipping container.

These things were made to hold about 30 tons of whatever needs to be shipped and fully loaded, stacked 8 high on ships to be transported around the world. Truthfully, these things changed the way global trade works. Ships come into port fully loaded and spend less than 24 hours getting unloaded and reloaded. It’s amazing.

The first thing to notice is these things are made of steel. Steel can be cut and welded. In the picture above, the containers are hooked together, but when they get welded together they are a really strong single unit. In fact, they’re ideal for building an underground house because the weight of four or five feet of dirt on top is nothing compared to what they were designed to hold.

A second critical piece of building material is the bridge panel. These are lengths of prestressed reinforced concrete that engineers build bridges out of (among other things).

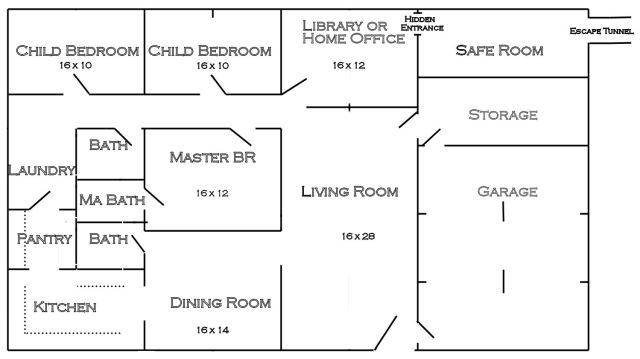

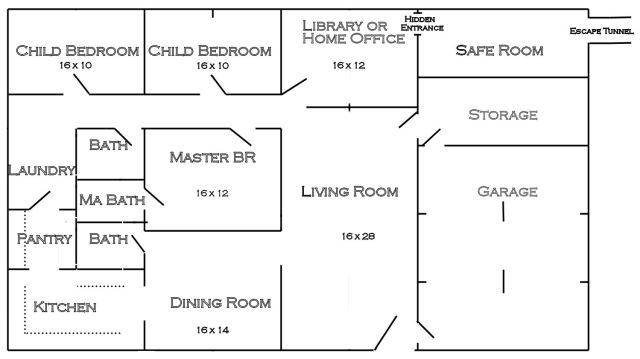

Let’s start with the design of a 1900 square foot home made from six 40-foot “high cube” shipping containers. A normal 40-foot shipping container has outside dimensions of 8’x8’x40′ which means a ceiling of a bit over seven feet on the inside. The high-cube containers have exterior dimensions of 9’6″x8’x40′ which means about 8′ 10″ for the ceiling height. That’s more in line with standard residential construction.

This home is 48’x40 feet in exterior dimensions, with the bottom facing the south and a wall of windows on the dining and living room and more standard windows for the kitchen. Keep in mind, this is a simple floor plan. The children’s bedrooms could each hold anywhere from 1 to 4 children with lots of room for their stuff. The master bedroom and bath aren’t huge, but what’s the point of designing a home for sybaritic excess if most of your time will be spent working somewhere else? This home can be built for under $60,000 and a 20% down payment is only $12,000. The only problem is finding a lender, because this isn’t “normal” housing and they worry about the resale value if the home has to be foreclosed on and sold.

I believe it’s possible to get a lender to give such a home consideration due to the very low cost to build and the fantastic energy savings, but it just depends on how anal they are. If a bank won’t lend, there are a number of private lenders who can and will lend with a well-written loan proposal. In this case, being able to show the low cost, energy savings and other advantages will go a long way toward convincing them. A reasonable family budget demonstrating that such a home could be easily paid off even working a low-wage job will probably do the trick.

One of the neat things about building this way is the home can be built as modular units, pre-wired and pre-plumbed. If you look at the plan carefully you might be able to tell that the second container from the left is the only one that contains plumbing, with all three bathrooms and the kitchen sink and dishwashers all contained in that container. This makes building the home far simpler to build than a “normal” home, in which one has to wait until the home is under roof before putting in the wiring and plumbing. What this means is the home could quite literally be built over time with a pay-as-you-go approach.

A crane will be required to put the units in place, but an empty shipping container only weighs about 8000 pounds so figure one in which finishing work has been done will weigh no more than 10,000 pounds. That’s only five tons. This means that two containers can be welded together and a crane can still easily lift them to put them in place. If the containers are properly placed on a good support when they’re delivered, fitting them together correctly can be accomplished with 8-ton bottle jacks. Once welded together, the sections that need to be cut out can be removed and finishing work can be accomplished.

In the plan above, notice that almost all the work will be in the left one third of the home. In fact, the middle third and right third are basically just removing and installing walls. Because of the corrugation of the steel walls, running the electrical and water lines is easy to do before putting the drywall on. Quite literally, this is a home that could be semi-finished by a single person in less than a year before being lifted into place and welded together.

If desired, three 20-foot containers could be positioned perpendicular to the home to make a two-car garage with 10’x24′ parking bays. That would add to the cost of the home or it could be added at a later date without any problem, but the point is this could be considered a “starter home” that has a simple design and provides enough room for a growing family for years to come. Five 20-foot containers gives the home a garage, storage area and a private space if it’s desired. Something like this.

That plan has a safe room and an escape tunnel, which isn’t a bad thing to have in our most interesting of times. The nice thing about this is the garage, storage space and safe room will cost out at about $15 per square foot, or an extra $12,000. That extra 320 square feet of storage and safe room space could always be finished out as living space, bringing the home up to 2200 square feet. It’s rather easy to build an escape tunnel out of three-foot steel culvert, but that costs out at about $25 per foot just for the pipe, so 400 feet of escape hatch tunnel will set you back about $10,000. All that together would bring the price of the home to somewhere in the neighborhood of $82,000.

For those preparing for the zombie apocalypse, the ultimate security measure is a couple of precast concrete panels that can be raised quickly to seal off the front of the home. This isn’t nearly as difficult as one might think, because it isn’t that difficult to dig a couple of pits for counter-balance weights. A 24×9 4 inch thick concrete panel only weighs about 10,000 pounds, or five tons. That’s the same as a 4 foot by 4 foot by 4.5 foot block of concrete. A lesser means of security can be had by taking steel panels removed from the interior of the home and crafting them into rolling steel shutters that close off the front of the house on barn door hangers.

One note on safe rooms and escape tunnels. I realize that some readers of this blog might be tempted to do something contrary to the laws of the land with such a hidden room, and might even figure that running banks of metal halide lights would make up for the lack of other electrical usage and not show an inordinate power consumption; and the escape hatch could be used to vent interesting smells out into the woods.

Listen carefully. If the home is hooked to the grid, it will have a smart meter, which will be able to tell what the power is being used for. The only way to defeat this is to run the incoming power through an inverter into a battery bank and back out on the other side. Such a battery bank would provide backup power during power outages and would allow the installation of solar panels or wind generators if wanted. It also makes efficient use of a generator. As with any such endeavor, unless it’s for personal use, the problem isn’t the job, it’s the company you have to keep.

The escape tunnel should always go downhill away from the house to prevent water infiltration. It’s possible to run the first section downhill for 40 to 50 feet to a sump with a drain, before going uphill with it, but God help you if your drain becomes clogged and the tunnel fills with water at the low point when you really need it. Recumbent bicycles and specially built skateboards can travel quickly through such a tunnel. Anyone who ever shows up at your home with evil intent will not have looked at the land registry before coming, so a little creative landscaping can give the appearance that a property line is much closer than it is. For homes on large tracts of land, a hedgerow that defines the yard likewise serves to restrain movement, channel the intruders and keep them focused on a rather small piece of terrain. In more residential settings the escape tunnel could literally go to another building several hundred feet away that appears to belong to someone else.

There is another type of tunnel that’s useful above ground. Plants like Washington Hawthorne, floribunda rose, acacia, osage orange and others all produce lots of sharp thorns and can form an impenetrable hedge. It isn’t unusual to see a treeline overrun with such plants and planting these bushes three to four feet apart and later pulling the tops together so they grow together can leave a hedged in tunnel underneath if care is taken to keep the interior trimmed. This was a favorite of mine as a child, when I took old woven fencing wire and created arbors which were quickly overrun by honeysuckle and wild blackberries. Carefully trimming fields of fire later in the season made these the ultimate deer-hunting blinds. I strongly favor protecting the exit point of your escape hatch with a hedge of protective plants that will prevent anyone from getting close to it.

For those not so inclined to wild scenarios, a simple escape hatch can utilize a short piece of culvert and a ladder that goes straight up, out of the house onto the top. The only problem is if there’s a fire, it creates a wonderful chimney effect to fan the fire. Not that there’s much to burn in an underground home, which is constructed of steel and concrete. Drywall doesn’t burn and one would have to work pretty hard to get the home on fire to the point it did some serious damage. However, the problem with fires is smoke inhalation and even a small fire can kill the occupants.

One of the critical points to an underground house is air flow. There isn’t a lot of room for standard HVAC ductwork, so the solution is to go with a high velocity mini-duct system which uses 3″ tubes instead of standard ductwork. this allows almost inobtrusive ducting that allows a constant flow of air through out the home. Standard homes leak air from the outside all over the house. Underground homes don’t, so care must be taken to keep the air circulating and a supply of fresh air coming in. If the builder installed an escape tunnel, that can be rigged up to bring in fresh (earth temp) air, but a fan is required.

Another critical point to these homes is insulation. Use sprayed on closed-cell urethane foam insulation sprayed on the outside of the house, three to four inches of it. This will ensure there is never any condensation on the ceiling or walls of the house. Failure to do this will result in a home that over time is uninhabitable due to the condensation and resultant mold growth. On the inside, the walls must be covered with drywall or some other wall covering because the steel reflects too much sound. I suppose cloth wall hangings such as tapestries would work as well or even better though, but I’ve noticed that women like things to look “normal” even when they aren’t.

One other critical point is drainage. Build the home into the side of a hill, and I don’t mean at the bottom. When the site is excavated (like any residential construction) the water and sewer lines need to be dug in first. In addition, gravel and perforated pipe needs to be installed to ensure that any water infiltration that makes it under the house is drained away downhill.

One of the big decisions is whether to put the containers on piers or a slab. The slab will be more expensive and has to be completely level, but piers work just as well if not better. As long as the house is level on a solid foundation, it isn’t going anywhere. What is critical is a monolithic foundation that supports the corner pillars of every container. Piers will suffice to support the floor rails. Overhead, a 4 inch reinforced slab will distribute the load and prevent the ceiling from buckling from the weight of the earth, or one can use precast reinforced concrete panels that have the advantage of being pre-stressed. These have the advantage of being trucked in and stored until needed, put into place with a crane and immediately sprayed with foam. With proper preparation one could literally put the modules in the ground, put the roof in place, foam it and have it covered with dirt in a single day.

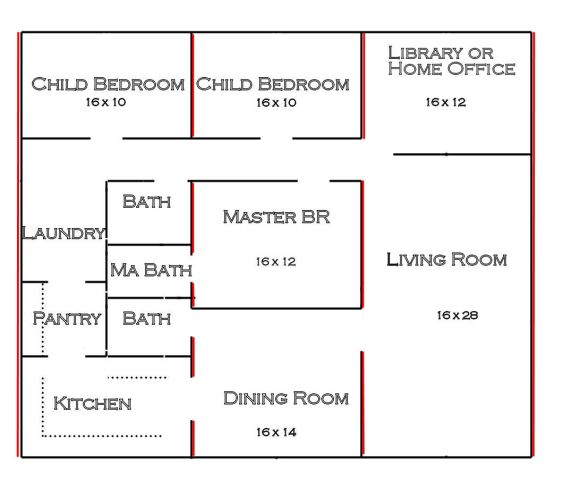

Back to our simple house plan, a good way to support the overhead load is to have a four-inch gap between the three joined 2-container units and fill the gaps with concrete. Everywhere you see a red line represents a 4 inch concrete support wall, which means no extra reinforcement is necessary on the sides of the containers. The back of the house has corner pillars every eight feet so very little extra reinforcement is necessary there.

Shipping containers were designed to support weight on their corner pillars, not on the roof, so in order to keep the dead load of earth overhead, reinforcement needs to be provided. Concrete is a very cheap way of doing this. In fact, for remote sites renting a large concrete mixer that mixes a yard at a time might be the best alternative to having concrete trucks deliver it. Not as easy, but not nearly as expensive either.

This post wasn’t designed to teach you how to build an underground home, but I did want to make a few points about how they’re constructed and the benefits of living in them. Essentially, with a good supply of water these are comfortable, safe and effective homes with no electricity at all if they’re designed right. Tornado and storm proof, convenient fallout shelters, soundproof and mostly bulletproof, a lot can be done with a house like this.

7 thoughts on “Underground Houses”